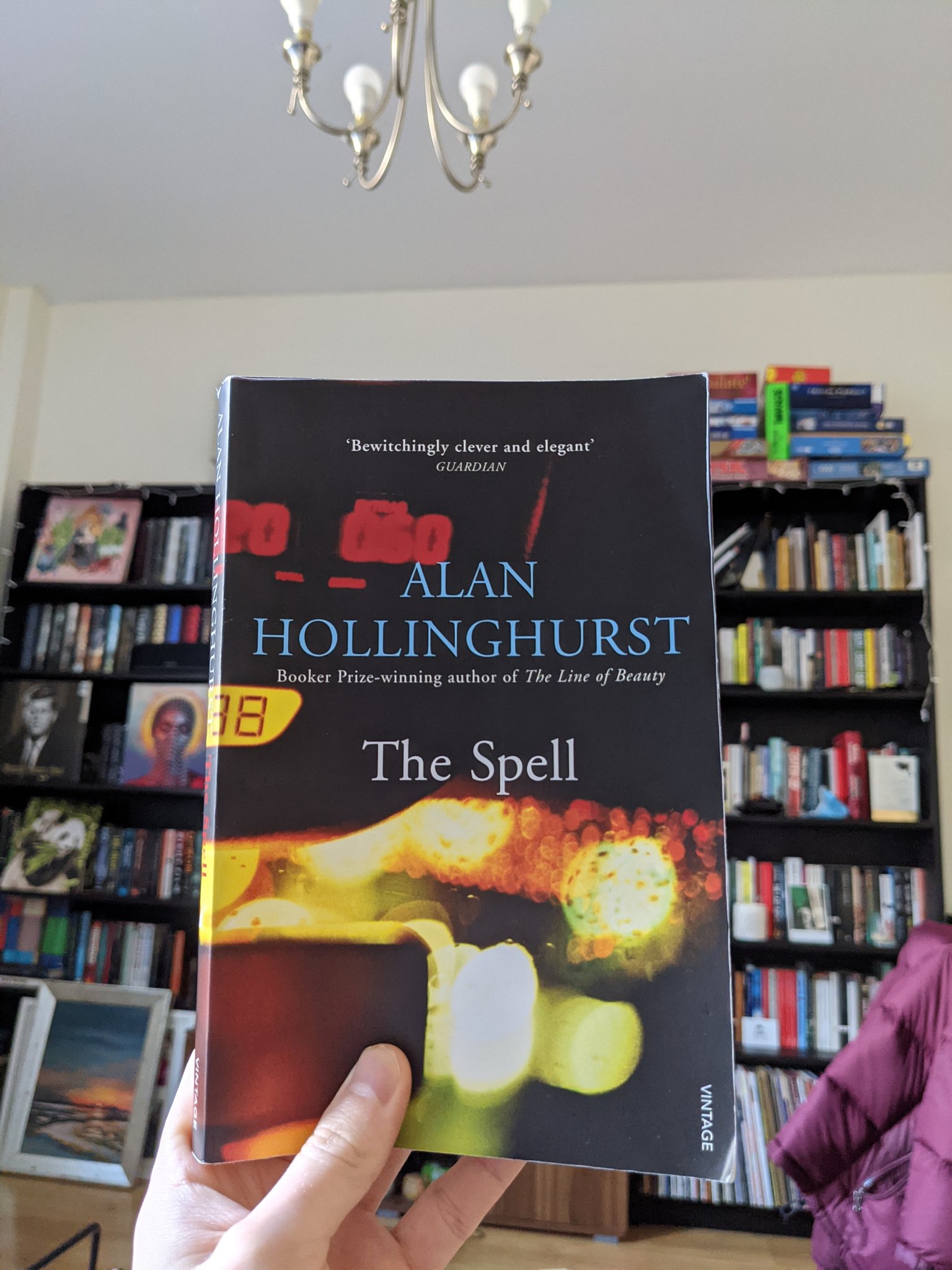

Alan Hollinghurst’s short 1998 “comedy of sexual manners” is not as magical as one might have hoped. Whilst witty in parts, its disjointedness and total lack of characters to care about leaves it feeling flawed and notably more frivolous than the author’s other more impressive works.

When Alan Hollinghurst won the Booker Prize for The Line of Beauty in 2004, the eternally subtle Daily Express announced the news with the headline “Booker Won By Gay Sex.” This cringe-inducing dismissiveness aside, Hollinghurst, like it or not, has established himself over the last thirty years or so as one of Britain’s leading gay writers. For his part, the author told the Guardian in 2011 that he “spent 20 years politely answering the question, ‘How do you feel when people categorise you as a gay writer?’ and I’m not going to do it this time round. It’s no longer relevant,” though he admits that he is “not sure my heart would be completely in” writing a novel with no gay characters or gay themes.

The Spell includes very few non-gay characters. Indeed, one of its four protagonists, Danny, realises in Dorset that he is “so conditioned to a world in which everyone was gay that he found it hard to bear in mind, down here, a hundred miles from London, that almost everyone wasn’t.” Where other Hollinghurst novels often concede a heterosexual intrusion into the homosexual world depicted – the gay-bashing scene in the otherwise unrelentingly gay The Swimming-Pool Library (1988), The Line of Beauty’s constant tightrope walk between the ‘proper’ and the decidedly improper – The Spell is a markedly lower-key affair.

Almost all of the issues encountered by the four gay men The Spell concerns – Alex, Justin (Alex’s ex), Justin’s new boyfriend Robin, and Robin’s son Danny (with whom Alex proceeds to fall in love) – are caused by one or more of the other three. The problem is, with all four either slightly pathetic or simply quite nasty, and each monumentally more shallow than they profess to be, one finds it hard to care much for any of them. Themes like revenge and betrayal are here so ubiquitous that the reader becomes numb to them, and the novel thus slips into dangerous territory: ‘show, don’t tell’ is one thing, but when the reader would rather you actually do neither you’re in trouble.

Of course, this style – showcasing characters of little redeemability – has worked many times before, either with anti-heroes or with farce (Hollinghurst is clearly going for the latter here), but it is difficult to tell in this novel whether the narrative is quite as dismissive of the characters as one feels it ought to be. Sometimes, it feels instead as though the novel is pleading with its reader to remain engaged with the tribulations of its four protagonists as it rushes between perspectives: bored of this character? Okay, what about this one, then?

Alex, for example, swallows one pill of MDMA (to which he is introduced, middle-aged, by the youthful Danny) and almost immediately recants his love of Shostakovich and purchases a CD named “Monster House Party Five”. This is surely just a little lazy, but the novel doesn’t have time to show subtle changes in character, and therefore hurries things along as though that is simply how they would happen, rather than, as Hollinghurst does so wonderfully in The Line of Beauty, allowing the dust to settle and carefully observing it as it does so.

It is hard not to wonder, with this novel about half the length of Hollinghurst’s others, whether it could not have worked better by focusing on only one of its four protagonists, and indeed why it is shorter in length than his earlier and later novels. The answer, possibly, is that the characters just aren’t quite interesting enough. Their relationship – beautiful boy sleeping with dad’s ex, everyone basically fine with it, ‘family’ gatherings a-plenty – is so bizarre that it verges on silly, making otherwise sincere moments feel the opposite. It really is the case that the least interesting thing about almost every scene tends, unfortunately, to be the protagonist to whom the scene is ‘happening’.

Hollinghurst is, though, as Dwight Garner puts it in a New York Times review of The Sparsholt Affair (2017), “one of the great noticers.” His ability to describe things otherwise unacknowledged is wonderful: a place of significance to a previous relationship is “left,” by Alex, when passed with his new boyfriend, “like any of those unspoken sadnesses or unguessed embarrassments that one partner keeps from the other for ever.” Equally, the inconsequential is made, in a sentence, to seem vast: Robin thinks “of that other day, at the far end of summer, when a little shift occurred in the weather, that might have been nothing, a morning’s chill after weeks of glittering heat, but was in fact the airy chink through which the autumn came pouring, with its vivid forgotten lights and ache of inexact memory and surprising sense of relief.” This is poetry.

It is in scenes with large groups of people that Hollinghurst really excels, though, and in one of the novel’s primary events – a birthday party held for Danny – he portrays excruciatingly an interminable conversation Robin falls victim to with one of his son’s friends, a spiritualist who believes he has – via a medium – spoken directly to Arthur Conan Doyle. Conan Doyle, he explains, “has a very fine voice,” and has informed him helpfully that he is “not really gay. I just happen to be attracted to certain men,” as well as that he “had been a sixteen-year-old fish-seller in the Holy Land at the time of Jesus Christ.” “You’d never suspected?” Robin quips.

Such scenes are characteristically funny, but as a satire, the novel is just not quite comical enough. Every sentence in The Line of Beauty reads as though written with a bemused raised eyebrow, and it works perfectly. Here, the reader is never quite sure whether they are in on the joke or if, indeed, there is a joke to be found at all. The character of Danny – youthful, attention-seeking, partying, part-time drug addict – is a caricature, fine, but Alex – heartbroken, snobbish, sensible, malleable – is ridiculous in a completely different way. Are we seriously to believe the two would ever really fall in love? And if so, surely we are expected to feel sorry for Alex (the novel’s most sympathetic character) when it all goes wrong? Only, his sheepishness is so frustrating, and the inevitable so… inevitable, that this simply doesn’t happen.

The Spell fails as a successful satire because it is frequently unclear exactly what it is supposed to be satirising. Late on, the novel tells us Danny “wanted to touch [Alex] consolingly, but also to push him off the fence.” This is how one feels, often enough, reading the book itself. Reluctant to take a stance, it finds itself lurching into tedium: it stares at the reader, but neither winks nor smiles. In drama this is fine. In satire, it is fatal.

Perhaps the novel is most disappointing because, with knowledge of the work that follows and precedes it, it feels like a missed opportunity. “A tightly-wrapped Hollinghurst novel, under 300 pages, depicting ‘romance and drugs, country living and rough trade’? Great!” But if anything, it makes a reader even more appreciative of the sprawling splendour of works like The Line of Beauty and The Swimming-Pool Library.

This short book is a misstep and, whilst occasionally typical (read: delightful) in style, it should not be considered a primer for the author’s other works. That being said, this is the author’s third novel, and we are now awaiting his seventh. Since 1988, it has become clear that he is not just one of Britain’s great gay writers, but quite simply one of Britain’s great writers. That it is the lively, and frequently unabashedly bizarre gay world on which he casts his witty but delicate eye is, surely, a bonus.